Defining itself as a “record on celluloid”, Dziga Vertov’s 1929 silent documentary film Man with a Movie Camera consciously avoids the trappings of story through a lack of intertitles, scenario, or dramatic conventions. One version of the original Russian intro translates: “This experimental work aims at creating a true international absolute language of cinema based on its total separation from the language of theater and literature.”

Despite the claim, Vertov does not avoid the “language of literature” completely, beginning his film with a clearly narrative montage portraying the preparation of a cinematic performance in a movie theater. However, he then transitions into atomized images of everyday objects and activities in an attempt to flee conventional coherencies of narrative sequence. By realistically portraying the manner in which fleeting moments of attention create a kaleidoscope of moment and memory, Vertov attempts a picture of the mind before Freud’s ego narrator manipulates fragments of image into sense.

Some years earlier, Dadaists had begun defying conventional coherencies by taking language and meanings from one context and inserting them in absurd frameworks; by moving outside conventional use of media; and by defying norms in general. In this period, Hans Richter experimented with relationships between painting and film, which Richter explained as an interest in discovering where “cinema can fulfill certain promises made by the ancient arts, in the realization of which painting and film become close neighbors and work together.”(Art & Pop Culture)

Like Vertov, Richter consciously disregarded narrative flow. But rather than using fragmented montage to disrupt conventional narrative portrayal of everyday reality, Richter focused his films Rhythmus 21 and Rhythmus 23 on the study of abstract spatio-temporal rhythms.

In examining this interaction between painting and film, Richter was challenging a conventional understanding of both. Similarly, Vertov’s attempt to discover the “nature, properties, and functions of the camera” and investigate its manner of seeing challenged a “narrative” understanding of everyday reality. However, it is not only convention being challenged in these experiments, since any experimental investigation of media employs our own pre-existing patterns of sight, perception, and interpretation.

In this sense, any experimental investigation of the camera’s manner of seeing or the interaction between image and motion involves our own pre-existing, culturally trained faculties of perception and understanding. In studying media, we also study ourselves. In playing with film, artists re-theorize perception through the invention of new experience. And in this sense, artistic experiment challenges not only existing paradigms of form or media understanding but reveals fundamental tensions between acts of perception, expression, and interpretation.

Norman McLaren’s work in abstract animation builds on the avant-gardist joy of experiment, freedom of play, and drive toward discovery. As an artist of the mid 20th century, McLaren focused not only on spatio-temporal rhythms of image, but the capacity of film to create conversations between abstract images, movement, and music.

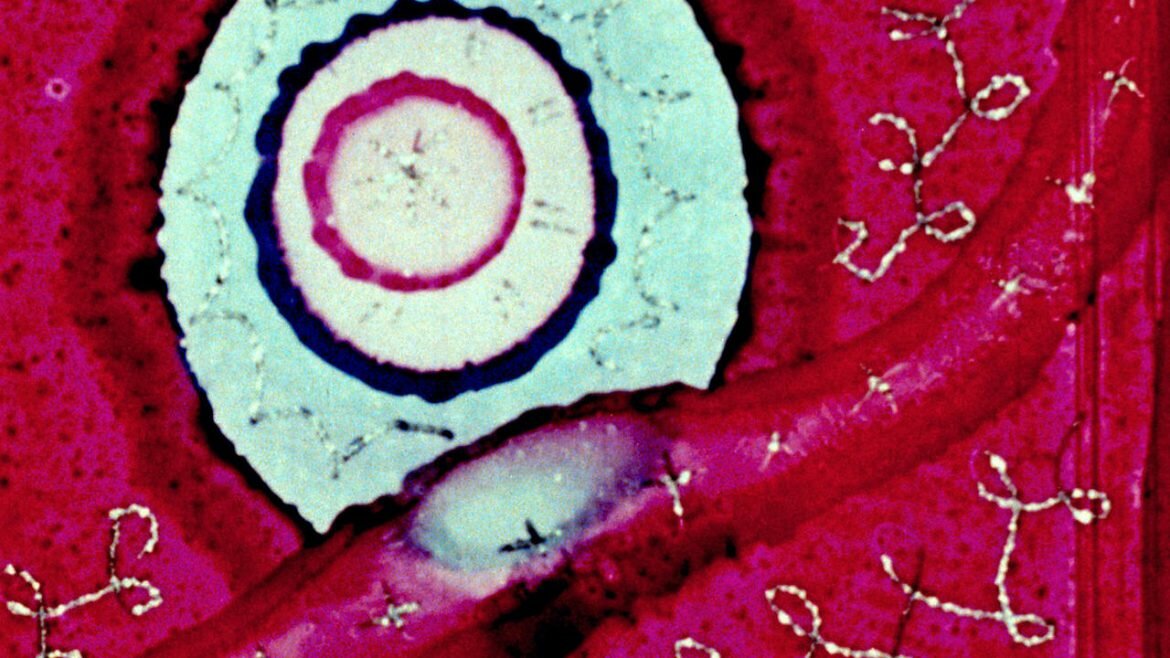

In Begone Dull Care, McLaren divides the film into two different types of improvisational jazz, fast frenetic passages, a passage with strong elements of boogie and smoother, and more delicate conversations between individual instruments. The images shift dramatically with the music. In the fast-beat sections, explosions of pattern cover the screen in crisscrosses or wiggling organic shapes. Short-toothed bars flashing on screen characterise the piano; notes chase each other or clench in momentary union. Surfaces of over-saturated colours and textures cover the screen like a drumbeat backbone; frenetic runs on the keys wind in and around backgrounds; more black screens are interrupted by the garish stripes, cross-weaves or odd feathery, scribbly beats that dart like bugs across the screen. As the music breaks into quieter, melodic conversation between individual instruments, the background turns black. Notes are revealed as vibrating strings, piano notes are rain drops blown by wind, fireflies, or fiery drips from sparklers that break into fluidly dancing fragments in syncopated runs.

What is the relationship of poetry to music, not just to rhythm, but to images, sensory impressions, nonlinear, non-narrative, associative, cerebral, rhythmic embodiments, heartbeat, eye-blink, finger-twitch, or toe-tap? What is the relationship between bodies in motion and rhythms of life or character of experience? The basis of narrative is the embodied consciousness and McLaren’s experimental animations use camera, soundtrack, and play to explore sensory-based realities as well as media.

If we are not convinced of this aim by viewing the film, we must be convinced by the film documenting McLaren’s experimentation with painting sounds directly on film. The analog portrayal of sound on film invites us to a very cool synesthesia, a touch of the Muses of language, sound, and visual imagination talking to each other.

(Sources: Art & Popular Culture; Senses of Cinema; Interfilm)