“In a time of universal deceit – telling the truth is a revolutionary act.”

— George Orwell

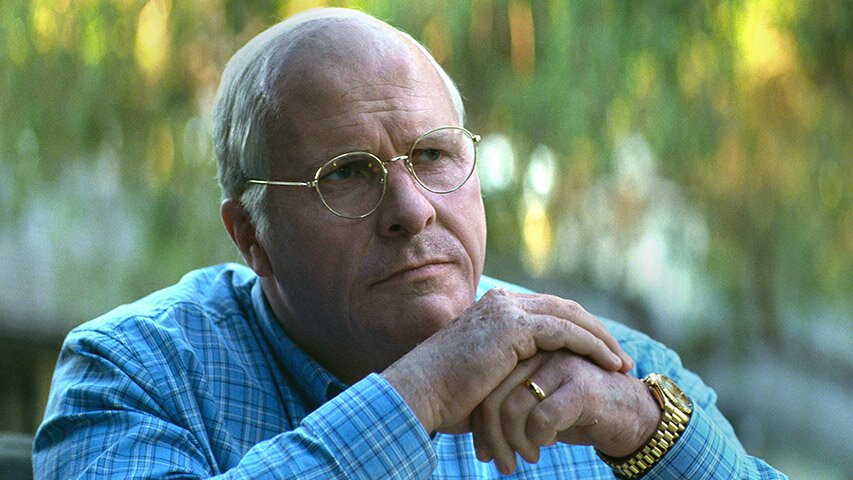

What is the truth? Does it even exist? The thrilling polemic in this year’s Berlinale, Vice from Adam Mckay is a comedic expose on the path to power which examines the culture of 21st Century American Politics through Shakespearean verse. McKay’s film, much like his earlier work (The Big Short, 1995) exposes the tension between the imagined reality that we think is real versus the truth. In Vice, McKay digs for the truth behind the Cheney’s ruthless rise to power within a serpent’s nest of corporate dynasties and family conflicts.

It is a systematic culture of corruption that allowed a Wyoming reared, Yale dropout, working dead-end jobs to flourish and become the most powerful Vice President and megalomaniac in the history of the United States. The first glimpse we see of Cheney is in 1963 Wyoming, as an inebriated twenty-two-year-old behind the wheel, his face smashed from a bar brawl, soon to be pulled over and locked up by a policeman. It is evident that Dick Cheney would not have amounted to much were it not for his wife, who regaling the horrific flashbacks of her abusive father, demanded “Either you have the courage to become someone or I’m gone.”

A clue to this incredulous rise of Cheney becoming someone is provided by McKay who theorizes and expertly details a classic Shakespearean power dynamic where Machiavellian wife Lynne Cheney (Amy Adams) is pulling strings behind the scenes to ensure her husband, Dick Cheney (Christian Bale) (the ruthless Richard III archetype) ascends to the throne. Importantly, the medieval devils in Shakespeare often had a comic element to them, so too does McKay embrace the form with witty morsels such as Lynne declaring that in an era “Where women are burning their bra’s in New York, women in Wyoming are wearing them!” Her message is clear, conservatism and servitude are the principal politics of the day.

The film depicts Washington DC as the ultimate battle ground for Cheney to begin his technocratic odyssey. Cheney begins as an intern in 1968 for the ex-captain of the Princeton wrestling team, Congressman Donald Rumsfeld, (Steve Carell) who instructs Cheney to “be silent, to obey and to be loyal.” The aesthetic of brotherhood and privileged ivy league haircuts are intercut with speedy edits of fly fishing, horse-back riding, tasselled moccasins and ranch style mansions creating an atmosphere of patriarchy at its most powerful. These are the “dedicated and humble servants to power.” Cheney assumes the role of an architect who begins building a system which ultimately results in giving unlimited power to the presidency.

Cheney shuffles along patiently through the gilded halls of Washington and is slowly pulled into the inner lair where he is appointed the youngest ever Chief of Staff to President Ford and allocated a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives. Resulting in a power couple, Lynne becomes chair of the National Endowment for the Humanities. The gala dinners are exclusive and lavish, a fortuitous breeding ground for political favours and it is here the spectator first meets the drunk George W. Bush (Sam Rockwell) whose nepotistic dad happens to be president. It’s the 2000 election that sets Cheney’s intergalactic rise on fire, with him assuming the military, energy and foreign policy responsibilities, fanning the flames of right-wing media platform Fox News and imposing regime change on Iraq, whilst brokering access to its oil. All, this on behalf of a “green” George W. Bush.

It’s not only the rise of the politicised machine that McKay captures in this film with the effects of its unsavoury economic policies, it’s also the personal toll on his health and his family. The metaphor presented on-screen is that of the bloated catfish, trolling the waters for his next victim, who turns out to be his own daughter. Mary Cheney, his second born, is thrown under the Wyoming campaign bus to further the family’s political legacy. On the mouthpiece of propaganda, Fox News Mary’s sister, Liz Cheney denounces gay marriage and thereby discards her lesbian sister’s identity. The invisibility of lesbians as a non-category worthy of human basic human rights is a moment of personal truth for the Cheney family, who have ultimately lost their humanity in their relentless pursuit of power.

A combination of stylistic edits, grouped and stitched together provide the pace and fervour of the film. Various pop cultural backdrops flash before our eyes in rapid succession, the BudWeiser ‘Wassup’ commercial, Survivor reality TV contestants and Pop Idol TV show judges are woven into images of President Saddam Hussein, air raids on Cambodian villages, charred human corpses, waterboarding terrorists and the aftermath of the Iraq War. We become participant observers in the evil as McKay attempts to form a connected whole between the collapse of privacy, fair news, torture laws and our own complacency. It is this thematic incoherence which exploits the possibilities between photographic realism and dramatic illusion, and the result is psychological.

The emphasis here from McKay is ensuring a certain amount of shock value by the blatant abuse of power we are witnessing in the white house. As Naomi Klein explains in her book The Shock Doctrine, “Countries are shocked — by wars, terror attacks, coups d’état and natural disasters.” Then they are shocked again — by corporations and politicians who exploit the fear and disorientation of this first shock to push through economic shock therapy. People who “dare to resist” are shocked for a third time, by police, soldiers and prison interrogators.” We are encouraged to peer through the haze of shock and arrive at a certain phenomenal truth. McKay’s montages are evidence of feeling and ‘Affekt’ as if he too set out not only to characterise but to record the monstrosities of this power trip towards a fascist government.

The system is engineered to favour white, power-hungry men, yet in true Shakespearean form, kings ultimately descend into disgrace and defeat. As Dick Cheney breaks the fourth wall in the film’s climax, his anger is palpable, “You chose me and I did what you asked.” Whilst America and the world discovered their narcissistic selves reflected back at them through the world-wide web and got increasingly distracted with reality television, a sociopath slowly climbed to the most powerful position in the United States of America. Writer and Critic Pauline Kael surmised in her 1975 review of Nashville “The picture says, this is what America is and I’m part of it.” There is a fine line between comedy and malice and this film prompts the spectator into existential self-examination to ask, am I a part of it?

Is there a murderer here? No. Yes, I am.

Then fly. What, from myself? Great reason why –

Lest I revenge. What, myself upon myself? (5.3.184–86)

– Richard III