Camp is a certain mode of aestheticism. It is one way of seeing the world as an aesthetic phenomenon. That way, the way of Camp, is not in terms of beauty, but in terms of degree of artifice, of stylization. – Susan Sontag Notes on Camp 1966

When Susan Sontag described and put a name to the sensibilities of ‘Camp’ in 1966 she captured a ‘badge of identity, the ideas (the intellectual history) and the behaviour (social history)’ of an epoch of largely homosexual, gay men. In contrast to ‘Camp’ and it’s bias towards ‘the love of the theatrical, exaggerated, unnatural’, very little has been dissected aesthetically and exclusively by women for homosexual women. Rather, on the contrary, being Lesbian and its mode of aestheticism has been defined mainly in terms of beauty as ‘butch dykes or pornographic nymphs’ in main-stream media. This has resulted in the invisibility of an authentic ‘badge of identity’ and stylization for Lesbian women.

Isabel Coixet’s Elisa & Marcela is the portrayal of Lesbian love set in the late 19th century Spanish city of La Coruña between Elisa Sánchez Loriga (Natalia De Molina) and Marcela Gracia Ibeas, (Greta Fernandez) which blossomed into the first-ever recorded marriage between two women. “It took ten years to come to the screen. People didn’t really want to touch it and they didn’t really understand it,” says Coixet of her difficulty getting this true story of ‘Elisa & Marcela’ made. Coixet exploits the romantic love between these two women through gothic architecture, the delicate violin, the searching piano and the expansive aestheticism of 19th century wilderness.

The word Lesbian is derived from the name of the Greek island of Lesbos. Home to the 6th-century poet Sappho, famous for her ‘Lyrical’ ideas, behaviour and poetry. It is this ‘Lyrical’ sensibility and taste, this expressive, poetically inspired, sentimental and emotionally charged, romantic love, typically pursued by two women which Coixet’s latest film based on a true story, ’Elisa & Marcela’ manages to capture effortlessly. Adrienne Rich in ‘We cannot rely on Existing Ideologies’ says “Lesbian existence comprises both the breaking of a taboo and the rejection of a compulsory way of life. It is a direct or in-direct attack on male right to access to women.”

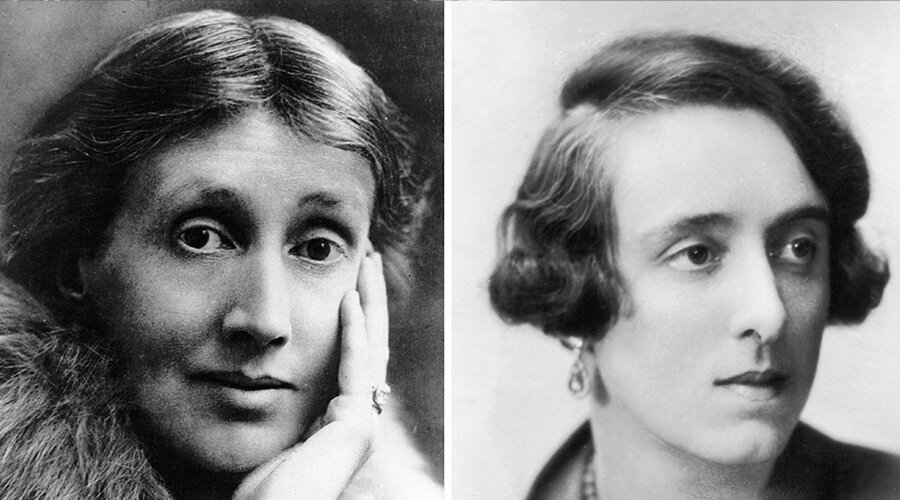

The story begins in 1898, in a girls’ college run by nuns, “the brides of Christ” in La Coruña. When Elisa and Marcela first lay eyes on each other, its lust at first sight, the clue of seduction evident in their starry-eyed gaze. Marcela’s suspicious father (Francesc Orella) soon forbids her from seeing Elisa and ships her off to another school in Madrid, he also instructs her that she is primarily at college to “learn just enough, but not too much” and that “some books bring nothing but trouble.” We witness heterosexuality being forcibly and subliminally imposed on women. In the lyrical communicative inspired style of Vita Sackville-West and Virginia Woolf, the two begin writing passionate love letters to each with Elisa declaring that “she dreams of her even when she is awake.” The same emphasis on the overwhelming power of love appears in many of Sappho’s songs.

Cut to three years later, Elisa and her beloved Marcela are both primary school teachers in a small village outside La Coruña. Coixet captures the tender sexual connection between two young women, with a handheld camera and in delicate, deliberate slow motion. Lesbian sex in all of its Sapphic inspired feminine glory. The tender yet deep kisses turned desirous for more, lingering bites and the hunger of craving this illicit love. Germaine Greer tackles the fascinating topic of female sexuality in ‘Our Bodies’ and says, “The female is considered as a sexual object for the use and appreciation of other sexual beings, men. Her sexuality is both denied and misrepresented by identified as passivity.” What the ‘Lyrical’ eye appreciates and which Coixet captures is that the slow, soft deliberate touch of a woman is inherently erotic due to its slow, deliberate nature. Lesbian taste is above all a mode of preference for sensuality, devoid of male gaze, it’s confident, coded in action and deconstructed, with the female form at its core.

In order to find acceptance from hostile locals, Alisa cuts her hair short and returns in June 1901 as ‘Mario’ to marry Marcela. The newlyweds try to fit in and adhere to village life, but are soon ridiculed, shamed as “Tomboys” and physically assaulted. Rejected by conservative Catholic Spain which at the time, was as Susan Walter describes “essentially a man’s land, few are the women who have emerged from the quiet life of home and church into public positions.”

The pair flee to Portugal where arrest ensues and Elisa faces charges of transvestism, blasphemy and identity falsification. The local newspaper prints the story of two jailed married women and the scandal is immortalised into the history books. The film’s handsome cinematography, shot in black and white, is from newcomer Jennifer Cox who captures the natural splendour of Galicia through the rain-soaked roses, budding chestnuts, new-born snails and sumptuous freshly caught octopuses. Coixet seems to place ‘The Love that dare not speak its name’ gracefully within the lush forests and wide open rivers, it’s a refined form of attractiveness, a love of the natural, previously unseen in Lesbian cinema.

Where does one begin to define Lesbian cinema? Misrepresented, vilified, repressed and perhaps most importantly invisible? Lesbians have been depicted mainly for male consumption; as crazy in delusional relationships “Heavenly Creatures” (Peter Jackson, 1994) as butch, cocky dykes in “Set It Off” (F. Gary Gray, 1996) as helpless, conversion victims “But I’m a Cheerleader” (Jamie Babbit, 1999) and more recently glorified pornographic temptress in “Handmaiden” (Park Chan Wook, 2016). In the last two years, we have witnessed a glut of Lesbian Cinema with “The Favourite” (Yorgos Lanthimos, 2018) and “Disobedience” (Sebastián Lelio, 2017) both featuring Rachel Weisz and failing to grasp the subtle essence of Lesbian commitment opting instead for a caricature of repression and gloom rather than expression.

Coixet’s sensitive understanding of the Lesbian need for discretion is accurate, as the film depicts the delicacy and the dreamy devotion beneath female love. As Audre Lorde writes in Your Silence Will Not Protect You “For each of us women, there is a dark place within where hidden and growing our true spirit rises, beautiful and tough as chestnut, stanchion against nightmares of weakness” Coixet attempts to shine a light on these ‘dark places’ because they are ancient and hidden, yet they have survived and grown despite the darkness of patriarchy.

The film’s pace is unhurried, lacking aggression and violence which mirrors the core of Elisa & Marcela’s tenderness for each other. Coixet’s love for and appreciation of film history is well-known, her fascination with aesthetics in ‘Elisa & Marcela’ sends a stylistic ripple effect through this story. The use of the iris shot feels slightly voyeuristic, inviting the spectator to gaze through a spy-hole into an unseen, untold and previously forbidden story. The audience’s gaze is corralled.

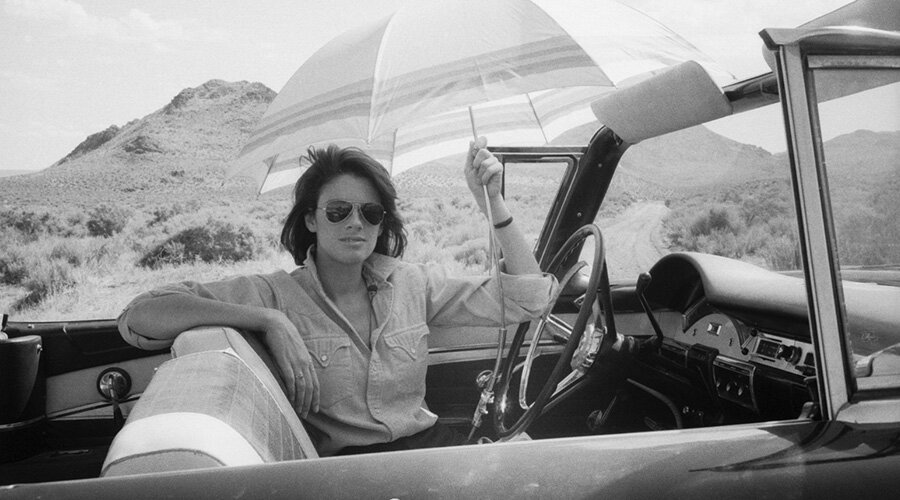

This film’s truth is that it captures the inherent loneliness of Lesbians forced to become self-reflective early, from childhood becoming acutely aware of society around them by observing their place outside of it. Comparable to the ground-breaking classic “Desert Hearts” (Donna Deitch, 1986) with its sweeping visuals and female characters that don’t end in tragedy, this was a film where Lesbians could see a sliver of themselves on the big screen. Instead of swaggering, cocky, butch masculine coding, we are instead presented with poise, the inner imagination and an appreciation for purity and pleasure.

Coixet reflects ‘Lyrical’ Lesbians with artistic sensibilities, which allows for lucid representation and provides proof that this type of love exists in the world. The message is an empowering one, Lesbians are women in possession of their own sexuality. If ‘Camp’ is in the clouds, then Lesbians are down to earth, rooted in nature, singing with their hands in the soil and their hearts filled with poetry. Lesbian love rejects the vulgarity of an institutionalised heterosexual emphasis on screwing, shagging, poking – built around the tool of the penis. Lesbians treat their vagina’s like the Temple of Venus, lined with the petals of a full blown rose. ‘Elisa & Marcela’ is a critical story within the barren canon of authentic Lesbian intimacy, aesthetics and identity. The film gather’s a genuine testimony of exile and determined adoration, which still sits rather uncomfortably alongside the heteronormative gender politics of contemporary society.

And her light

stretches over salt sea

equally and flowerdeep fields.

And the beautiful dew is poured out

and roses bloom and frail

chervil and flowering sweetclover.

– Sappho