What really makes a cinematic movement? We all know about collectives of film-makers with a connected conscience, rebellious political motives, and reactionary auteurs united in challenging the films of their time, but can a truly inspirational movement even exist without first recognising the country it has originated in? Is the language of that country integral to the movement, a subconscious narrator of film-making? If we start acknowledging linguistic relativity in the shaping of a national cinema, we will understand how those movements stayed so important and representative of their country. We will understand how they enlightened audiences to such a huge impact in countries that did not speak that language, or more importantly, think that language.

In basic terms, linguistic relativity is the principle that language itself determines our thoughts, decisions, and outlook, or at the very least influences them. So if our own thought processes in everyday life are limited by the language that we think in, how can that not affect what we create? To make this simple, I have taken three major cinematic movements that changed film forever. They are The Golden Age of Japanese Cinema, The French New Wave (La Nouvelle Vague), and New German Cinema (Neuer Deutscher Film). My argument is that these movements could never have happened outside of the country that they originated in because of the language they were conceived in.

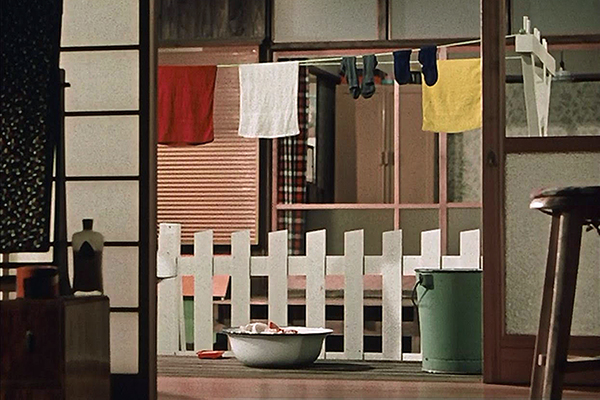

Countries all over the world have words that are technically untranslatable in other languages, but what is most fascinating is that it is not just the word itself that has no translation, the feeling or event it is used to describe may not have been seen as significant enough to have its own title. Take ‘Boketto’ for example, it is a Japanese word with no English translation, but basically means ‘to gaze vacantly into the distance without thinking.’ In England the closest thing we have to that is probably ‘smoking’. If ‘Boketto’ is in your language, you are aware of its existence, it is a part of your culture, you would not question someone standing on their own gazing vacantly, because what they are doing is understood. The pensiveness of Japanese Cinema in the Golden Age is not a gimmick, it is not a rebellion to fast pace, it is the cinematic understanding of ‘Boketto’. Take Yasujiro Ozu and the conception of ‘Pillow Shots’. Noel Burch coined the term that describes the gentle shots of everyday life in between Ozu’s exquisitely composed scenes of narrative. These ‘Pillow Shots’ are often misconstrued as ‘random’ or ‘out of place’, they are usually simple shots of

mountains or railroads, or even of clothes hanging on a line (Good Morning, 1959), and are only random because we do not live by Japanese linguistics and the beauty of ‘Boketto’. Ozu is visually blessing a Western audience with this term, without even telling us what it is.

Another example is the Japanese word ‘Yugen’. It loosely translates to ‘a profound, mysterious sense of the beauty of the universe, and the sad beauty of human suffering’ and is consistently present in the films of Akira Kurosawa. To understand that the universe itself can trigger an emotional response and that it can be reflected in the actions of a human being is fundamental to the stunning cinema of Kurosawa. He uses the rain to enhance the sadness of a character when words are just not enough, like in Rashomon (1950) and Red Beard (1965), or the dramatic wind in No Regrets for Our Youth (1946) that intensifies human weakness but still exposes its very beauty.

The French New Wave adopted the same form of linguistic relativity in their works too, and serve as a wonderful education in film and language. The french expression ‘La Douler Exquise’ is essentially the exquisite pain of wanting someone you can never have, but will attempt to be with anyway. It is this term that serves as an emotional plot line in Francois Truffaut’s Jules et Jim (1962) and is why the film feels so natural, despite the unusual story it never feels contrived. The female protagonist Catherine is desired by both Jules and Jim, they obsess over her free spirit and goddess-like beauty, Jim wants her but she marries Jules, then post-war, Jules informs Jim that she has been repeatedly cheating on him and later allows Jim to marry Catherine. They both appear to eternally want her but can not really have her because Catherine is emotionally unavailable to them. Later in the film after the split of Jim and Catherine, it is then Catherine who is in ‘exquisite pain’ and wants Jim back even though he has moved on. ‘La Douler Exquise’ is one simple expression that encapsulates the entire picture. If you look at Wes Anderson’s re-make of the story for Prada, it appears overly stylistic and contrived, not only due to the cinematography and trademark image, but also because the ménage à trois concept is indeed very odd and does not seem to be understood as a natural series of events to a director without the French way of thinking, although beautiful, Anderson’s version is somewhat an American parody of French Cinema.

Another example is the French concept of the ‘Flâneur’, an aimless wanderer of the city. Look at the opening to another of Truffaut’s films, Le Quatre Cents Coups (1959), the city of Paris is shown to us in montage form with a travelling camera, like the audience are themselves exploring the city and simply taking in the sights in order to understand a way of life, before embarking on the adventures of Antoine Doinel. These are not filler shots, they are a beautiful expression of surroundings, of allowing us to be observers without rush or guilt, they allow us to be the flâneur.

There are other simple terms in the French language too, such as ‘Dépaysement’ – the physical or mental disorientation of being in a foreign environment. It is this word that I think drives the sheer poetry and truth in Alain Resnais’ Left Bank New Wave film Hiroshima, Mon Amour (1959). You could also look at ‘Retrouvailles’ – the happiness of meeting someone you have not seen in a long time. Without this concept, the instant trust and connectivity we feel in Ma Nuit chez Maud (1969) by Eric Rohmer would be lost. Protagonists Jean Louis and Vidal have not seen each other since they were children but welcome each other instantly, and we are assured that the lack of awkwardness is due to the happiness and comfort they feel, despite their conflicting attitudes to nearly everything else. It is because of the retrouvailles that this film so easily delves in to the main action of the story.

Inspired by The French New Wave and the Oberhausen Manifesto of 1962, New German Cinema arrived and delivered a new national cinema to Germany. To fully understand key works of the movement, such as the flawless Alice in den Städten (1974) by Wim Wenders, one must look at the language of the country. The word ‘Fernweh’ is essentially a longing for a place that you are not currently in and translates as ‘Distance Pain’. Throughout Alice in den Städten each character is trying to find a way out of where they are, especially protagonist Philip Winter who travels America and finds nothing but consumerism and emptiness. His feelings to leave America could easily be misunderstood as homesickness to an English audience with no concept of fernweh, but it is not a longing for Germany that he feels, just a way out of wherever he is, he struggles to find his purpose. The same feelings can be applied to Alice, who wishes to leave America and later Germany due to her longing for Amsterdam, Holland. In fact, this film is a perfect example of a production that could have only been made by a German director. The phrase ‘Inner Schweinehund’ can also be applied to Philip Winter and depicts the feeling of subconscious inertia or involuntary apathy, a voice that tells you to leave everything to the last minute, that nothing is really worth doing, and Alice seems to be the direct antithesis to Philip’s Inner Schweinehund.

Finally, Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Angst essen Seele auf (1974) is the perfect visual representation of ‘Weltschmerz’, which directly translates to ‘World Pain’. The movie shows a couple becoming the victims of ageism, racism, violence, exhibitionism, nationalism, class, illness, judgment, and all because of a romance deemed unconventional to everyone but Ali and Emmi, the couple in mention. The weltschmerz is a feeling that the world is not living up to what you thought it would, and their relationship is a constant battleground for the anguish in the world around them, and eventually takes its toll on them, until they realise to ignore this world pain and focus on their love.

In conclusion, I feel that to truly understand the importance and influence of national cinematic movements, we must observe the country of the film’s inception, and specifically the language of that country. Linguistic relativity is integral in comprehending the genius of these movements and the fluidity of the films themselves. The words and phrases untranslatable to an English-speaking audience is one of the reasons that films in foreign tongue have a special resonation in us; as well as being an enjoyable audio-visual experience, they are an education and an awakening in emotion itself.