“The world in which we live is reflected in contemporary cinema. The personal is political, the old slogan from the 1968 Women’s Lib movement is experiencing a new currency.” – Dieter Kosslick, Festival Director

This year’s 69th Berlinale claims to reflect the world we live in by putting women in charge of the camera. The Competition’s line-up boasts that it’s not only about the #Metoo movement in Hollywood or equal opportunity for female directors, but rather an entire examination and much needed revision of traditionally male, pale and stale cinema. How many times does women’s history have to repeat itself?

Of the seventeen films in total submitted into the Competition, which are vying for the Golden and Silver Bears, seven were directed by female filmmakers. This represents 41.2 % and is the figure that has been used to promote the competition this year in most press releases. However, if one digs deeper into the Berlinale Gender Report, into the coveted category of direction, on the basis of current films in the Berlinale programme, 34.8% of overall directors are women, and 60.9% of the entire competition is still wholly dominated and directed by men.

It is apt that the Golden Honorary Bear of the Berlinale 2019 Competition for lifetime achievement goes to a female icon, Charlotte Rampling. In the 58 years of the Berlinale, only six (9,7%) women have been honoured with this award, in comparison to fifty-six (90,3%) men receiving the Honorary Golden Bear. A retrospective glance over the last 68 years of the competition reveals that women have gone from an invisible 0.7% of total female-directors in competition to 99,3% male-directors between 1951-1960, to an almost visible 18,9% total female-directors compared to 81.1% male directors between 2011-2019.

What are categories for and why are they important? Categories tell us what gets included and excluded. As Kathleen Stock, a Philosophy Professor from The University of Sussex explains. “The category “female” is also important for understanding the particular challenges its members face, as such. These include a heightened vulnerability to rape, sexual assault, voyeurism and exhibitionism; to sexual harassment; to domestic violence; to certain cancers; to anorexia and self-harm; and so on.” Looking at this year’s female filmmakers represented in the Competition, we witness an exploration of the female psyche under various oppressive conditions.

In the spirit of the festival embracing gender diversity, Berlinale’s opening film “The Kindness of Strangers” is from Danish Director, Lone Scherfig. She exhibits a keen sense of character and loneliness, as Scherfig describes the film as offering the spectator a glimpse into the unseen subway and soup kitchens, “The New York under New York.” It is her third film with Director of Photography Sebastian Blenkor who weaves the fragility of the characters into the machine like abyss of New York City. At the centre of this domestic abuse story is Clara (Zoe Kazan) on the run with her two boys from a terrifyingly violent cop husband Richard (Esben Smed). The whiff of male brutality permeates the screen, Scherfig attempts to steers us towards forgiveness rather than isolation and despair, by shining a light on systemic issues and capturing a future with forgiveness at its centre. As Scherfig explains “You see Americans reaching out to help needy people in a way that I really admire and I think we could learn from – not politically, but as individuals.”

Isabel Coixet’s magnificent Elisa & Marcela is the portrayal of Lesbian love set in the late 19th century Spanish city of La Coruña between Elisa Sánchez Loriga (Natalia De Molina) and Marcela Gracia Ibeas, (Greta Fernandez) which blossomed into the first-ever recorded marriage between two women. “It took ten years to come to the screen. People didn’t really want to touch it and they didn’t really understand it,” says Coixet of her difficulty getting this true story of ‘Elisa & Marcela’ made. Coixet exploits the romantic love between these two women. Coixet’s sensitive understanding of the Lesbian need for genuine representation is noteworthy, as the film depicts the delicacy and the dreamy devotion beneath female love.

Teona Strugar Mitevska’s God Exists, Her Name Is Petrunya, an oppressive black comedy about a spirited yet unemployed Macedonian woman who spends the night being grilled by male police for participating in a men-only religious ceremony. An educated history major, a subject which has no place in a country whose political disputes date back to 1991 and the break-up of Yugoslavia. Macedonia was a Yugoslav republic and adopted the name Macedonia when it became an independent nation, yet Mitevska’s delivers a portrait of a brave young woman defying a country clinging to sentimentalism and an outmoded past. Mitevska’s view on the male dominated world, “Because the world belongs to men; how many women scientists have been erased from history? How many are we only rediscovering now?” This is a feisty and melancholic satire questioning democratic change and the role of a conservative church and archaic media in suppressing change.

Marie Kreutzer’s The Ground Beneath My Feet, a securely controlled psychodrama which subtly draws the viewer into a woman’s efficient, ruthless and successful career. The examination into a society fixated on achievement reveals the fine line between sanity and paranoia, order and chaos. When Lola’s (Valerie Pachner) sister Conny (Pia Hierzegger) who is suffering from mental illness, attempts to commit suicide the film exposes the fragility behind trauma, loss and neglect. Lola’s growing sense of paranoia and suspicion of her own senses creates a synthesis of motion and truth for the audience, if they are willing to confront it. Kreutzer’s comment on creating characters with depth: “There are many flattened female figures, but also many flattened male figures. My claim to all my characters is that they must be three-dimensional and ambivalent – just like all of us. In this film, I was also concerned with the dark side that each of us carries, whether we are dealing with it or not.”

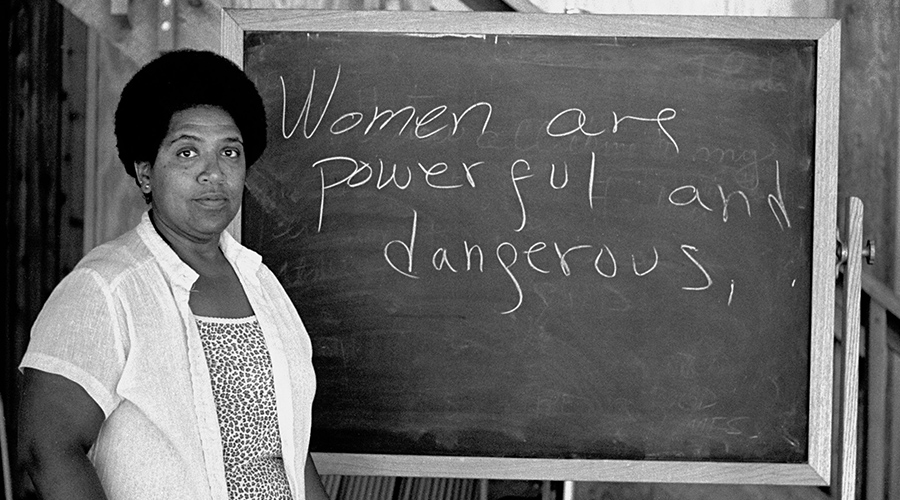

Each of these female filmmakers illustrates the vital role of stories in creating collective empathy to changing systemic cultural narratives, including patriarchy, racism and misogny. Ella Saltmarshe explains in the Stanford Social Review: “Humans have always used stories to make sense out of our chaotic world. Stories make, prop up, and bring down systems. Stories shape how we understand the world, our place in it, and our ability to change it.” If we use stories to change systems, then it’s critical that the stories curated are representative of the diversity of the world we live in order to foster community cohesion and engender empathy across minority groups and outliers. Should the stories continue to be dominated, directed and produced by men, what hope do the previously invisible communities have of being seen, understood and heard? As Audre Lorde said in 1979, “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House.”

It is imperative that we develop new tools, processes and systems of collective storytelling to navigate industrialised sexism. A critical part of this is identifying the outliers, the lesbians, the radicals, the poets and the minority groups to develop unifying narratives of different perspectives and variation to the custom Hollywood model. Without painting a consistent and equal representation of an alternative future, we are denying an accurate collective narrative. People can’t be what they can’t see, and it is cinema’s duty to provide a communal picture of reality, not a biased one.

Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex illuminates the underlying causes for this political submission, “Women lack concrete means for organizing themselves into a unit which can stand face to face with the correlative unit. They have no past, no history, no religion of their own; and they have no such solidarity of work and interest as that of the proletariat. The lived dispersed amongst the males attached through residence, housework, economic condition, and social standing to certain men – fathers or husbands – more firmly than they are to other women. The free woman is just being born. Rimbaud’s prophecy will be fulfilled, “There shall be poets!” What is certain is that hitherto women’s possibilities have been supressed and lost to humanity, and that it is high time she be permitted to take her chances in her own interest and in the interest of the all.”

So yes, the personal is political.