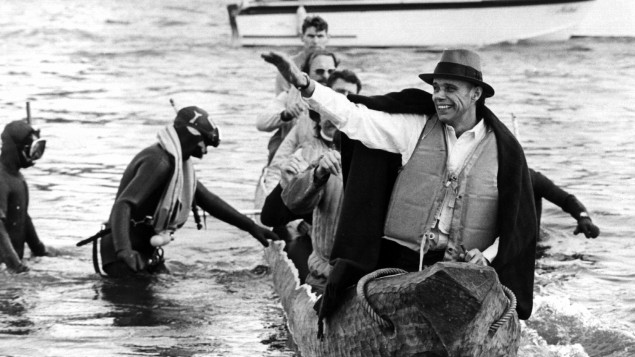

This film is about the artist of the 20th century, Joseph Beuys. Never heard of him? Most Germans, regardless of their level of education or their interest in art have heard of Joseph Beuys. Born in Kleve, he walked the earth like a shaman, dressed in a hat and a khaki fishing vest, offered healing thoughts, aktionen (happenings) and confusing installation pieces suggesting ways to heal a wounded post-war Germany.

His personal legend includes being a member of Hitler youth, a gunner with the Luftwaffe and getting shot down over the Caucasus. His pilot died but he survived and, according to his story (which is gently questioned in the film), the Tartars rolled him in fat and wool until he could be brought to a hospital. Consequently, fat and wool figure prominently in his work.Beuys shows you the man, his interactions with the press, his inner family life and the dilemmas he faced in his career: from youthful depression to starting a counter-cultural revolution, taking on 400 students at the Düsseldorfer Kunstakademie, to finally getting fired. Throughout it all however, his mantra lives on: “Jeder Mensch ist ein Künstler.”

Visually, the movie shows us pages and pages of photos which are then picked out and animated, bringing the specific time and place from the image to life, which is a stunning graphic achievement to say the least. The talking heads speak for just the right length of time, allowing us to understand who is talking and how they fit into the puzzle of his life.

If you have heard or read about Beuys, this is a chance to see some unusual, exclusive footage of him in action. We see him in a crowded room where he gathers up gelatine from the walls, pours it on himself and is later watered down with a watering can, before proceeding to converse with a dead rabbit, which proves all in all to be a very visceral experience as he plays with a limp bloody hare for the duration of the performance.

Moving pictures capture a clear sense of his radical mindset. He has a clear verbal arsenal to support his “expanded concept of art” and his desire to provoke a creative revolution. Moving images and his voice therefore make the viewing experience all the more dynamic.

He wanted a revolution – and found it within his obscure juxtaposition of objects which occasionally provoked laughter. Revolutions need laughter, he proclaimed. He wanted to create art that people not only wanted to participate in, but art that people ‘must’ participate in. Sounds like a grand statement, but coming from him and the way he is depicted within Beuys, while watching, it seemed almost feasible.