Films about the Black experience in America often mirror and rewrite mainstream cinema traditions. Spike Lee’s Da 5 Bloods enlists Apocalypse Now and The Treasure of the Sierra Madre as faded musical sheets on which to write a new, Black Valkyrie of the Vietnam War. Roberto Minervini, an Italian-born director living and working in the United States, favors a similar model in What You Gonna Do When the World’s on Fire?, though his approach is – quite understandably so – more muted and self-conscious. We haven’t seen this uncomfortably uncut style of filmmaking since Cassavetes’s claustrophobic 1960s phase and the raw, observational poetry of Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep. Falling somewhere in-between neorealism and cinema vérité, Minervini’s aesthetic runs the risk of masking the film’s dramatic subject under decorative scenes, but the way he applies it to the documentation of police racism and Black resistance turns the crisp black-and-white camerawork into an unnerving political tool.

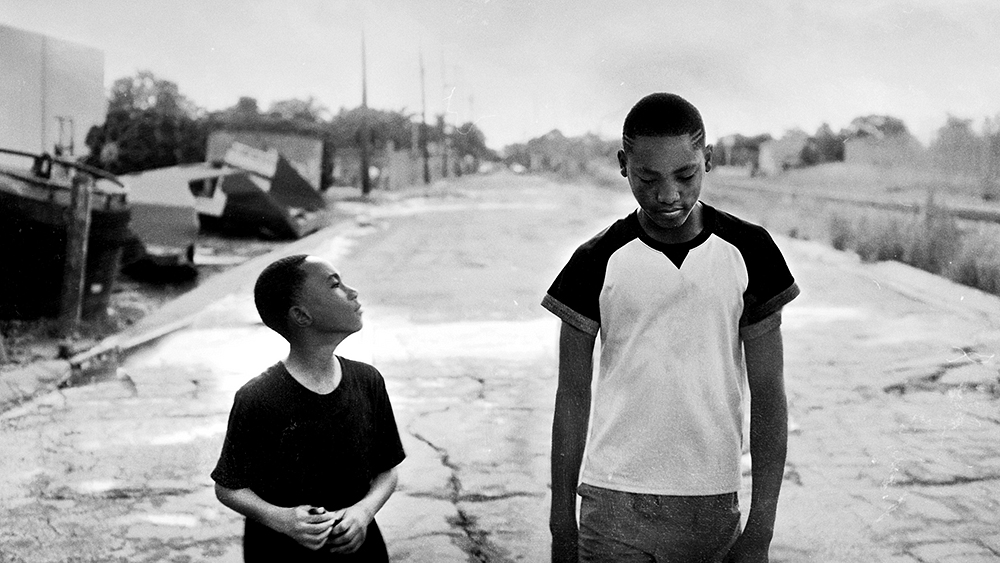

Set in Jackson, Mississippi and the historic neighborhood of Tremé in New Orleans, Louisiana, during the first summer of the Trump presidency, shortly after the Department of Justice decided not to file criminal charges against the police officers who shot Alton Sterling at close range after an altercation in Baton Rouge, the film leads the viewer to expect a solemn spiritual much like the Lead Belly song cited in its title. The opposite is the case. There is nothing redeeming about the story of 50-year old Judy Hill, a former drug addict struggling to put on a brave face while her bar business unravels; the 14-year old Ronaldo teaching his 9-year old brother Titus to fight, so he can defend himself until he owns a gun of his own; or the citizens of Jackson, too cowed by racially motivated violence to even open their door to the New Black Panther Party and its rifle-carrying militia, who keep knocking with the placid persistence of campaign volunteers canvassing for a dead candidate. At the time the film was shot, the decapitated, charred body of student Jeremy Jackson was found in a wooded area, after the family had discovered his head on the porch of his home.

With a striking sense of visual intimacy and the cadence of Black vernacular, Minervini’s film brings home just how indelible the trauma of slavery and oppression remains for ordinary African Americans – not the articulate senators and writers interviewed on TV, but the poor urban Black individuals trying to make rent in increasingly gentrified neighbourhoods or keep their kids on the straight and narrow. Lynchings, the KKK, and the torture of slaves combine to form the language in which members of this Black community most easily communicate and solidarize with each other. Figures like Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, Harriet Tubman, and Nat Turner appear so familiar to them as if they were still living just down the road. Yet the memory of Black heroes is anything but invigorating. Alongside the recent victims killed by police or White supremacists or both, the deified dead turn this iconic neighborhood into one big cemetery. It’s a heart-rending testimony to the afterlife of racist violence long after the shackles of slavery and Jim Crow have officially been shed.

The director’s unobtrusive technique amplifies the aimlessness of the lives we are privy to, and makes for uneasy viewing. While Minervini’s perspective is palpably sympathetic, it is not always charitable. He doesn’t shy away from showing us that these disenfranchised individuals, some of them ex-felons, are beset by resentment more than remorse, or that the sexual abuse the women describe occurred within their own families at the hands of Black men. The circuits of accountability are intricately entangled, and yet the film leaves us in awe of these Black lives: imperilled but defiant, both insecure and proud, humiliated by systemic disadvantage yet unashamed.

The film’s dilatory tempo dramatizes both the paralyzing effects of injustice and the difficulty of maintaining a purpose in a literally and symbolically arrested life. In lieu of narrative thrust, Minervini relies on confessional dialogue and shot length. One man tears up as he admits that he never expected to live beyond 23. In another scene, we are asked to consider whether reducing the charge for killing a Black person from murder to manslaughter dehumanizes the victim, as if policing entailed the kind of mechanical, socially sanctioned killing that happens in a slaughterhouse. And when the camera lingers on the unmoving face of Judy’s mother until flies begin to settle on her shoulders, we are reminded that in a nation plagued by racism, very little separates the living from the dead.

So why did this Black community open up so fearlessly to a White European director? As Krystal Muhammad, Chair of the New Black Panther Party, remarked last year in a discussion at New York City’s Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, the reasons have to do with the tendency of US media to depict her organization like a Black version of the KKK. Indeed, the Anti-Defamation League and the Southern Poverty Law Center, among others, classify the New Black Panther Party, which is also disavowed by leaders of the original Black Panther party, as a hate group. Confronted with accusations of racism and antisemitism, for members of this group – whose slogans, as witnessed in the film, include “Death to the Oppressor” and “Fuck the Black Police” – Europe is an ally in a never-ending global war for justice and self-determination. As anti-racist protests triggered by the death of George Floyd continue in the US, What You Gonna Do When the World’s on Fire? has the potential to foster an important conversation about how the enduring pain of injustice fuels Black nationalism around the world, and which means are legitimate in the fight against White supremacy, without succumbing to a vicious circle of violence.