In an interview with Anna Rose Holmer for the December Filmmaker Magazine, Greta Gerwig describes Louisa May Alcott’s 1868 Little Women as being about “art and women and money.” Gerwig’s adaptation of the novel articulates these very frustrations in a manner both authentic and cathartic. Amy, the youngest March sister and aspiring painter expresses her frustration at her self-ascribed lack of artistic talent. The family friend, Laurie, in an attempt to comfort her, asks, “What women are allowed into the club of geniuses, anyway?” Amy replies, “The Brontës?,” and cannot think of any others. Laurie follows up with the question, “And who always declares genius?” Amy replies, “Men, I suppose.” The gatekeepers of art still remain unchanged over a century and a half later. Female ambition, as evidenced in the recent American Democratic Party primaries, is to be viewed with distrust.

When I watched this scene for the first time on a typically rainy day in Seattle this past December, the theatre grew very quiet. The scene is heart-stopping in the way it is directed, acted, and photographed. Immediately after this piece of dialogue, a male member of the audience let out a loud belch, effectively ruining the scene for the rest of the (primarily female-identifying) audience. A friend in Frankfurt sent me a message a few weeks later, telling me she had finally seen the film, loved it, but her experience had been ruined by a man loudly sighing out of boredom throughout. It’s the ultimate cinematic manspreading - not only am I going to express my disinterest, I’m going to make sure you know it.

This show of disinterest stems not only from these anecdotal accounts. Following its U.S. release last December, Greta Gerwig’s recent adaptation Louisa May Alcott’s novel Little Women was received with buzz by film circles with what Vanity Fair dubbed the “little man problem.” Critics, primarily white and male, were not going to see the film. This demonstrated lack of interest translated, as predicted, into awards season with the film’s glaring absence from most award ceremonies’ Best Picture and Director categories. And these absences indicate that as much as the industry may pay lip-service to talk of diversity and inclusivity, not much has changed.

A great number of reviews have described Gerwig’s film as a modernized, fourth-wave feminist retelling of Louisa May Alcott’s 1868 novel. In a recent take for the Jacobin, “Little Women for the Lean-In Generation,” Eileen Jones rails against the “faux feminism” espoused by Gerwig. Jones never uses the word, but the review focuses mainly on Gerwig and her film’s lack of authenticity. (I wonder where this buzzword has come up in relation to women, expertise, and power in the United States recently?) Cassandra Neyensch in her review for Public Books expresses her disappoint with how she reads the film as different from Alcott’s book.

Certainly, the extent to which costume dramas could be radically feminist has long been debated, given the emphasis on the marriage plot. In a clever piece of narrative framing, Gerwig manages to even upend this particular convention. Gerwig spent a great deal of time researching Alcott’s letters and biography. The decision for Jo to marry Bhaer in the book came about from publisher pressure to conform to the marriage plot. (I always thought I was alone, but apparently Alcott’s nineteenth-century readers really didn’t “get” the couple either!) Instead of a pedantic, much older professor, this Jo gets Louis Garrel, but more importantly, she succeeds in publishing her own book. Allusions to the March family’s stance as abolitionists are made in one scene, though it admittedly could have been expanded. In fact, few costume dramas in recent years have succeeded in negotiating the intersections of race, class, and gender as Amma Asante’s fantastic Belle.

Ultimately, the issue with these two reviews, and the complaint about the “modernisation” of Gerwig’s Little Women in general results in their engagement with several tired tropes regarding literary and historical adaptations. First of all, the field of adaptation studies has largely shifted away from the emphasis on the “fidelity” to the source text. Moreover, several readings that Neyensch, and particularly, Jones make about the text do not hold up. Gerwig is a close reader. Second of all, it is largely acknowledged that a historical film/literary adaptation remains just as much a reflection of the period in which they are made as of the period depicted onscreen. That being said, I’ve read numerous interviews, where Gerwig and others involved in the production discuss their particular choices. They did their research.

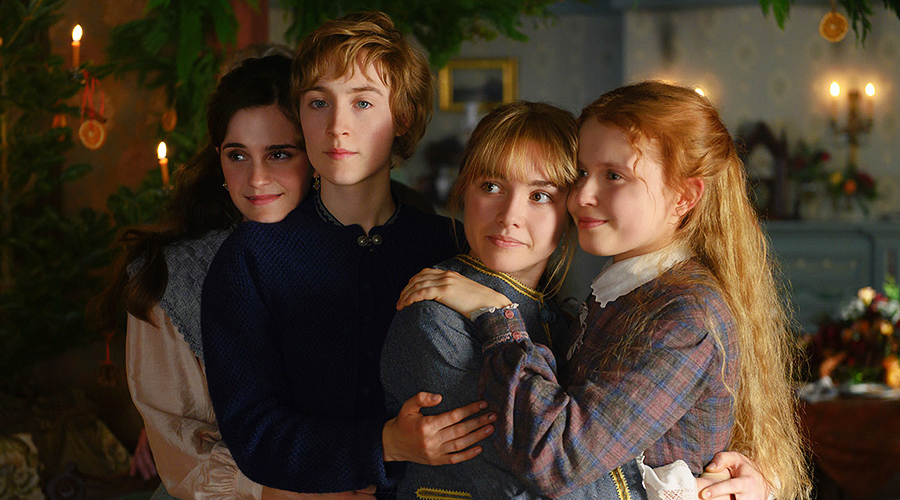

Like, Jones, I also grew up reading all things Alcott. (To further emphasize my authority on the subject, I have three sisters, too, and Gerwig’s depictions of the knock-down-drag-out sibling fight scenes are painfully accurate.) For a reviewer who takes Gerwig to task for an alleged lack of fidelity to the source text, Jones’ piece is glaringly messy and inaccurate. Foremost, Jones claims Gerwig does not emphasize the economic anxieties of the March family (lest we forget the core readership of the Jacobin). Jones takes issue with the richness of the colours of the March sisters’ clothing in the films, and Gerwig has often stated in interviews that costume designer Jacqueline Durran emphasised the fashion sported “bright” colours, even among the less well-off. (The photographs were black and white, not the clothing themselves!) Jones complains about the lack of emphasis on restrictiveness in women’s lives, aghast at a shot of Saoirse Ronan running through the streets sans corset. A quick word search of the source text reveals no mention of corsets, and a Google search reveals the Alcott family were against them.

Jones and Neyensch view Gerwig’s characterisation of Beth as a betrayal of the depiction of the nineteenth-century “Angel in the House.” The Angel in the House metaphor refers to a mid-nineteenth century Victorian poem by Coventry Patmore, where he describes the ideal woman as timid and subservient to men. The metaphor and its source poem do come in handy when introducing ideas about nineteenth-century gender roles in an undergraduate college course. Yet, it remains an oversimplification of complex and often subversive gender performances of that time period. Virginia Woolf wrote that killing the Angel in the House was part of the occupation of the female writer, and she knew women were already doing just that in the nineteenth-century. Alcott does describe Beth as “timid” and “shy,” but also states she “lives in a happy world of her own.” The former characteristics do not render her in the blank slate. If she exists in her own state of mind, why would Beth not be feeding her dolls at the breakfast table, like in Gerwig’s film? Beth is a glorious weirdo!

Jones and Neyensch certainly have the right not to like the film. Truth be told, as much as I loved the film, the 1994 version, still remains my favourite primarily out of nostalgia. Greta Gerwig’s films are slow burners, startling in their quiet radicalism. They speak volumes to her transcendent prowess as a filmmaker. Gerwig clearly knows her stuff-historically, cinematically, and politically. The male glance’s refusal to see it is, quite frankly, enraging.

I’m glad this movie brought Little Women back into the spotlight again